- Home

- Gustainis, Justin

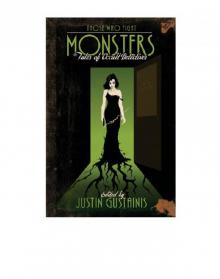

Those Who Fight Monsters: Tales of Occult Detectives

Those Who Fight Monsters: Tales of Occult Detectives Read online

Those Who Fight Monsters

Tales of Occult Detectives

Edited by

Justin Gustainis

E-Book Edition

Published by

EDGE Science Fiction and

Fantasy Publishing

An Imprint of

HADES PUBLICATIONS, INC.

CALGARY

Notice

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. It may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each reader. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of the author(s).

* * * * *

This book is also available in print

* * * * *

“From ghoulies, and ghosties, and

long-leggedity beasties, and things

that go bump in the night, Good Lord

deliver us.”

— Old Scottish prayer

“There are things that go bump in the

night… And we are the ones who bump back.”

— Professor Trevor Bruttenholm

Introduction: “Down These Mean Crypts a (Wo)Man Must Walk”

by Justin Gustainis

As the subtitle tells you, this book is devoted to stories of occult detectives, a term that I define fairly broadly — to include any fictional character who contends regularly with the supernatural. Thus, although not all occult detectives are monster fighters, all monster fighters are clearly occult detectives.

We decided to go with the present main title because Those Who Detect the Occult just didn’t have the same “zing” to it.

The character of the occult detective has been part of our popular culture for more than a century. The most comprehensive listing of supernatural sleuths can be found at G. W. Thomas’ “Ghostbreakers” website (occultdetective.tripod.com/all.htm), although it needs updating. Thomas lists 164 occult detective characters — in books, films, comics and television — appearing between the mid-Nineteenth Century and 1999.

From the beginning, (probably J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Martin Hessilius, in 1872), the occult detective often wasn’t — a detective, that is. He was often a doctor, sometimes a scientist, occasionally (as in the person of Abraham Van Helsing) both.

In modern fiction, the occult detective may be, among other things, a private eye, a police officer (in a universe that recognizes the supernatural), a reporter, a bounty hunter, a priest, a wizard/witch for hire, an antiquarian, an assassin — even a waitress.

As this collection shows, the contemporary occult detective takes many forms, and may be male (John Taylor) or female (Jill Kismet), human (Pete Caldicott) or nonhuman (Dan Hendrickson), professional (Marla Mason) or amateur (Kate Connor), a saint (Piers Knight, sort of) or a sinner (Jezebel), gay (Tony Foster) or straight (Quincey Morris), cop (Jessi Hardin) or criminal (Tony Giodone). But each shares at least two traits with the others: specialized knowledge, and the courage to use it. Thus, they have more in common with the hard-boiled private eye than the classical sleuth. The occult detective is closer to Philip Marlowe than Hercule Poirot, and today usually appears in stories that are more “hard-boiled” than “cozy.”

Classical detective stories were all about the puzzle, usually (if ungrammatically) expressed as “who done it?” Once the cerebral investigator solved the mystery, action was usually left up to the authorities (“Inspector, arrest that man!”).

But the private eye goes beyond mere deduction. He (or she) may investigate, certainly — examining evidence, interviewing witnesses, consulting experts to interpret what has been uncovered. But, having put the pieces of the puzzle together to form a unified whole, the private eye does something about it. The title of Mickey Spillane’s first Mike Hammer novel expresses this point clearly: I, the Jury. And although most fictional private eyes are not brutal vigilantes like Mike Hammer, they usually share his desire to act against the bad guys, once the latter have been uncovered; it is no coincidence that in The Big Sleep Philip Marlowe compares himself to “a knight in dark armor.”

This willingness to confront evil on its own terms is also characteristic of the occult detective, who knows that wooden stakes have other uses besides holding up tents, and wolfsbane is not just a pretty flower.

However, the occult detective is more than just a supernatural private eye. In fact, I would argue that he or she embodies some of the central roles found in any society.

The occult detective serves as a doctor, who brings specialized knowledge and skill to bear upon some affliction — someone who can diagnose the illness, treat it effectively, and propose effective preventative measures for the future.

The occult detective takes the role of a shaman, who understands the supernatural world and those who dwell within it. The shaman serves as a communication channel between the two worlds — and sometimes, even travels between them.

The occult detective is a hero, in the classical sense — an extraordinary individual who, with strength, skill, and courage, protects the community from those who would do it harm.

Small wonder, then, that the contemporary occult detective has found a home within the fiction genre (or sub-genre) known as “urban fantasy” —a term that usually refers to stories set in a world much like our own, but with the addition of a supernatural element.

Occult detectives predate the category “urban fantasy,” but then so does urban fantasy itself. The literature came first, the label sometime later. Applying the generally accepted definition, Stoker’s Dracula was urban fantasy — at the time it was published. The story depicts the actual Victorian world its readers lived in — with the interesting addition, however, of the undead.

The movie Ghostbusters (1984) also appeared before the common use of “urban fantasy,” but clearly falls within that category. The film takes place in a New York City much like the real one, except that ghosts and other supernatural creatures exist, posing varying degrees of danger to the populace — from slimy annoyance to the potential End of the World as We Know It.

The film’s opening theme asks, “Who you gonna call? And by the time the marshmallow man is toast, we all know the answer.

More than twenty-five years have passed since Venkman and the boys first strapped on their gear, but the essential question remains unchanged. Even in the 21st century, whenever demons walk the earth, werewolves prowl the countryside, or vampires ride the night winds in search of innocents’ blood…

Who you gonna call?

In the pages that follow, courtesy of some of today’s best writers of urban fantasy, you will find fourteen delightful, disturbing, and downright creepy answers to that question.

I hope you enjoy them.

— J. G.

Little Better than a Beast: A Marla Mason Story

by T. A. Pratt

“This is for you, Miss Mason.” Granger, the idiot hereditary magician of Fludd Park, handed a crumpled envelope across her desk.

Marla took the envelope, which was smudged from Granger’s mud-streaked hands, and hefted it. It was age-browned and soft, made of some heavy paper with a lot of cloth mixed into the fibers. “And what’s this?”

“It’s been in our house underneath the trees,” Granger said, smiling affably, face as broad and unsubtle as a snowplow blade. “In the safe, with a note, that said, give to the chief sorcerer of Felport on such and such a date.”

Marla frowned. There was nothing written on the envelope, and it was sea

led with several blobby hunks of wax. She could make out the barest shape of an impression in the central blob, maybe some kind of bird, a hawk or a crow, as if a signet ring had been pressed into the wax when it was soft, a million years ago. “This has been in your family, like for safekeeping? For how long?”

Granger looked at the ceiling and hummed and drummed his blunt fingers on the desk, which was how you could tell he was thinking. Marla didn’t have much use for nature magicians in general, and inbred nature magicians with an inviolate hereditary line of succession and a seat on her highest councils were even worse. “A long time. As many springs as there are days in a year, maybe much more.”

Three-hundred-sixty-five years or so, then? That would date this letter from the earliest days of Felport’s founding in the 17th century, back when it was nothing but a few settlers clinging to life. In those days Granger’s great-great-great-great-whatever-grandfather was just the sorcerer in charge of keeping the town commons and farmland healthy and green, long before the village became a thriving shipping and industrial center, and even longer before its recent rusty decline, an economic slowdown Marla was doing her best to reverse in her capacity as chief sorcerer and protector of the city. None of the city’s population of ordinaries, oblivious to the magic in their midst, would know the new biotech companies and urban renewal projects were Marla’s doing, but that was okay; she wasn’t in this job for the glory. She just loved her city, and wanted it to thrive.

“Any idea what the letter says?” Marla didn’t particularly want to open the thing. She’d had a bad winter, combating a plague of nightmares, along with the interdimensional invaders old Tom O’Bedbug still insisted were fairies from Faeryland, and she’d been hoping for a quiet spring. She didn’t think a letter from the early days of the city would be likely to contain good news.

“No ma’am, we were told to hold it, not read it, just keep it until such and such a date.” His beaming face suddenly closed down, smile gone like the sun slipping behind a mountain. “But I got distracted, spring is coming and times are so busy in the park, so such and such a date accidentally passed, some days ago, only as many days as I have fingers, about, not so many as could be, not too late, right?”

Marla picked up a letter opener shaped like the grim reaper’s scythe. “So I was supposed to get this a week or ten days ago?”

“Thereabouts,” Granger said, head bobbing, happy they were in agreement.

If I could fire him, or have him committed… But Granger was a powerful magician, in his way, and even if he wasn’t much use to the city’s secret shadow government of sorcerers, he mostly stayed out of the way in the park, and his elementals had been formidable warriors in last winter’s battle against the nightmare-things. She considered reprimanding him for not bringing the letter on time, but it would be like hitting a puppy fifteen minutes after it pissed on the carpet — the poor thing wouldn’t even understand what it was being disciplined for.

Marla used the letter opener to pry up the wax blobs, then unfolded the envelope, which wasn’t an envelope at all, but just a sheet of paper folded in on itself. The message wasn’t very long, but it said everything it needed to.

She came around the desk, shouting “Rondeau! I need you!” and clutching her dagger of office. This was going to be a bloody afternoon.

“Is everything okay?” Granger said, bewildered by her sudden action.

“Everything’s just beastly,” Marla said.

“The mother-effing beast of Felport,” Rondeau said, long strides matching Marla’s own as they hurried along the sidewalk toward the center of the old city, north of the river. This was a neighborhood of cobblestone streets and quaint crammed-together shops (many spelled “shoppe” on the signs, with the odd “ye olde” as a modifier), a touristy district where you could buy hunks of fudge as big as pillows and stay in a bed-and-breakfast where an early president had slept, once, allegedly.

“That’s what the letter says.” Marla frowned at the compass-charm in her hand, ducking into an alleyway that led, she hoped, to the tiny square that was the site of Felport’s founding. There was a fancier, more obvious Founder’s Square a few blocks away, with a monument, but she was dealing with magical rather than the municipal history. She wanted the spot where Felport’s first chief sorcerer, Everett Malkin, spoke the spells of binding that tied each successive chief sorcerer to the city, ritually entangling the strengths, weaknesses, and interests of Felport itself with its protectors.

“So, uh, what exactly is the beast of Felport? Werewolf, demon, undead mutant water buffalo? My grasp of local history is a little shaky.” Rondeau shifted the heavy shoulder bag Marla’d given him to carry, and things inside clinked together.

“Probably because you never went to school,” Marla said. Rondeau was her closest friend and business associate — he owned the nightclub where she kept her office, and they’d saved one another’s lives far more often than they’d endangered them — but he’d had a non-traditional childhood and never saw the inside of a classroom. “Nobody seems to know exactly what the beast was. In the early 17th century, Felport was just a trading post with a nice bit of coastline, good for loading up and emptying boats. People kept trying to settle here in greater numbers … and something kept killing them, even worse than the usual New World problems of murderous natives and disease and bad winters and starvation. Bodies would be found chewed up, missing certain necessary organs, like that, killed by something worse than bears, nobody knew what — some kind of beast. People started calling the place ‘the fell port’ — ‘fell’ as in dangerous, bad, scary — which is where the city got its name. Eventually a sorcerer named Everett Malkin came along, really liked the location, and convinced some settlers to join him, despite the region’s nasty reputation. He said he’d keep the beast of Felport, whatever it was, away. And he did. He was the city’s first chief sorcerer.”

Rondeau yawned. “I’m glad I missed school. That story was boring, except for the bit about dead bodies. So if Everett whatever killed the beast hundreds of years ago, how is it supposed to bother us today?”

“I didn’t say he killed it — he drove it off.” Marla stopped walking, looked at her compass charm, which was spinning wildly, and nodded. “This is the spot.” They were in a tiny cobblestoned courtyard, a pocket of forgotten space with only one alley leading in and out, surrounded by the windowless portions of various old brick buildings. A droopy tree grew in an unfenced square of grayish dirt, and a storm drain waited patiently to collect the next spring thunderstorm’s rain, but otherwise the courtyard was bare.

“So what now?” Rondeau said, flipping open his butterfly knife.

Marla shaded her eyes and looked at the square of sky above. Very nearly noon. “Well, if I’d gotten the letter a week ago like I was supposed to, I’d have this place surrounded with containment teams and every contingency plan imaginable, and I’d feel pretty well prepared after spending a few days reading Malkin’s old enciphered journals, and researching every conceivable theory on the beast of Felport. But, since Granger is an idiot and I had no advance notice, we wait for midday, and if something appears, we beat the shit out of it.”

Rondeau put down the shoulder bag and Marla sorted through it, taking out charmed stones, knives crackling with imbued energies, and even an aluminum baseball bat ensorcelled with inertial magic to give it an extra bone-shattering wallop. Finally, she removed her white cloak lined inside with purple, her most potent and dangerous magic, which exacted a terrible price every time she used it. She put on the cloak, fastening it at the throat with a silver pin in the shape of a stag beetle, telling herself she probably wouldn’t need its power. After all, how bad could the beast be? It was a beast. Sure, the stories said it was all kinds of unstoppable, but tales tended to grow in the telling, and four hundred years offered lots of time for embellishment.

After hefting the bat, Rondeau flipped his knife closed and put it away, choosing the blunt object over the razor’s edg

e. “Okay, you got a letter from Everett whatever saying he sent the beast of Felport umpty-hundred years into the future, and you might want to keep your eyes out for it. This raises a couple of questions for me.”

“Oh, good. I love your questions. They’re always so insightful.” Marla did a few stretches, her joints popping, then checked the knives up her sleeves.

“Number one: I thought time travel was impossible?”

“Traveling backwards in time is. Or, at least, no sorcerer I’ve heard of has ever cracked it. Some adepts say they figured out how to move forward in time, though it’s more like putting yourself off to the side in an extra-dimensional stasis, set to re-enter normal space-time at a later date, unaffected by the passing time. But not many try to do it, since there’s no way you can go back again after seeing the wondrous future.” She took a leather pouch over to the alleyway and emptied it, dumping a dozen thumbtacks and pushpins — all augmented with charms of snaring and paralysis — across the courtyard’s only exit, just in case.

“Seems like it could be a good trick for waiting out the statute of limitations,” Rondeau said, in the tone of voice that meant he was contemplating casino robberies.

Marla snorted. “Any sorcerer capable of going forward in time would have more elegant ways to avoid being arrested for something, Rondeau. It’s bigtime mojo. I couldn’t do it, and I can do damn near anything I set my mind to.”

“Too bad. It’d be nice to skip the occasional boring weekend. Okay, so my second question: isn’t sending the beast of Felport to the future kind of a dick move? Getting rid of your current problems and leaving it for your descendants to deal with?”

“Yep,” Marla said. “Everett Malkin was, by most accounts, a nasty piece of work. A badass sorcerer with a knack for violence and the interpersonal warmth of a komodo dragon—”

“Doesn’t sound like anybody I know,” Rondeau murmured.

Those Who Fight Monsters: Tales of Occult Detectives

Those Who Fight Monsters: Tales of Occult Detectives